Today, I welcome onto my blog, author Kat Redfern, who is here to share her thoughts and insights into writing myths and retellings!

How do you go about re-telling a fairytale or myth? Why would you want to? I can’t give you a general how-to guide, but I can share how I’ve done it, and what I think about it.

The two questions I start with both come down to why?

- Why do I want to re-tell one (or more) of the old, old stories at all?

- And why am I choosing this story (or mash-up of a few) in particular?

Starting with the first question why re-tell an old story? For me, this question has two answers.

One, I want to add depth and complexity to characters I was intrigued by as a child but now find one-dimensional. I want to know what Rapunzel did in that tower all day and how she managed to grow up vaguely functional despite the isolation. I want to know why the prince had to rely on a shoe to find Cinderella, rather than recognising her face.

The other answer was, when I started writing seriously a few years ago, I wanted some help with the story structure. I’m more of a discovery writer but I needed a very basic scaffolding to reassure me that there was a path ahead. I can now do this for original story arcs, but it was one less thing to worry about at the start.

Having the super-simple and flexible scaffolding of a Cinderella, or Sleeping Beauty, or Jack and the Beanstalk story can be incredibly reassuring when you’re setting out on a new novel quest. And, hey, if it veers off because your main character suddenly turns out to have super powers, or would rather adopt a cat and solve a crime with the annoying-but-attractive local police detective, who’s going to know?

In terms of the second question, and your specific story of choice, this is where it can get interesting. The stories I want to tell the most are the ones where the female character either has, or could have, some get-up-and-go.

There are some stories that come to mind straight away, although most of them aren’t well known: Thrushbeard, Donkeyskin, Vasilisa the Fair, East of the Sun West of the Moon, and Cupid and Psyche (for a left turn into Greek/Roman mythology).

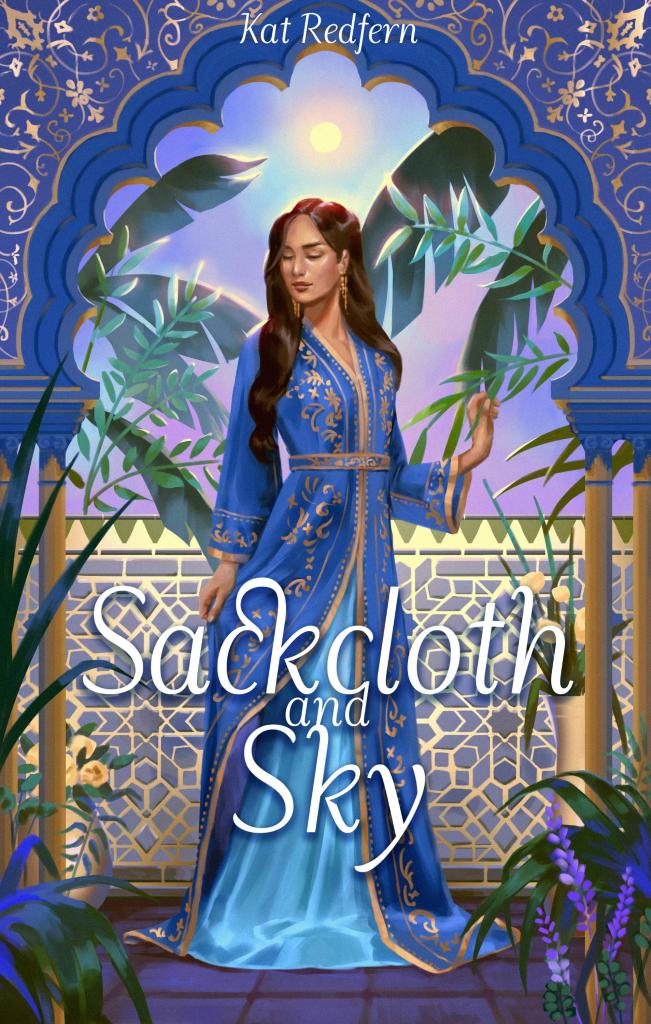

My novel, Sackcloth and Sky, is a retelling of the Donkeyskin fairytale (also known as Catskin, or Cap’O’Rushes). It’s a forgotten fairytale in the vein of Cinderella where the princess challenges her nasty suitor to make her four impossible dresses (three beautiful, one ugly), then disguises herself in the ugly one and gets out of town. She finds work in the neighbouring kingdom’s castle, turns up at three balls in the three beautiful dresses, prince falls in love, aaand we’re off into happily ever after.

So that’s kind of what I wanted to keep. What I wanted to change included:

- The nasty suitor (who is her own father in the original, just too yuk),

- Killing the poor donkey (or cats), absolutely not happening, and

- The insta-love based on nothing but good fashion choices.

Which opened up some fairly important questions.

- Who’s the nasty suitor?

- What form should the ‘ugly’ dress take?

- How do my two romantic leads meet in a way that feels like they can legitimately develop a relationship, or at least feelings for each other, prior to the balls?

- What on earth does my female lead actually DO in between scarpering and getting married? There’s not really much story in running dramatically through a forest, then hanging out in a castle scullery for however long.

- And, bonus question, how does the nasty suitor get their comeuppance? In the original(s), dad shows up to the wedding, realises it’s his daughter, sheds some repentant tears and everything’s fine and dandy. Nope, I’m not that nice.

Pulling this back to a more general approach, it can help to have an idea of the various ways your chosen story has already been retold, to give you an idea of which elements matter, and the different ways they could show up.

For example, in Cinderella, what does the glass slipper actually do? Could something else do the same thing, and be recognisable as the glass slipper element to those in the know? What if it was an animal they rescued together, who recognises its other saviour/friend. What if it’s a saying or lines from an obscure song where only the other person knows the next part? Would they work? I think so, depending on who and where your characters are.

I’m going to point you to a book I found brilliant for this, The Classic Fairy Tales by Maria Tatar. In this, you’ll find stories grouped by ‘type’ such as Beauty and the Beast, Snow White, Bluebeard, and so on. Each section starts with an essay, talking about how different cultures, and different times have produced stories that may differ in elements, but hold the same basic form. It then shares a collection of those ‘same same but different’ stories. As an example, the first section, Red Riding Hood, has seven tales that cover old stories from Europe, China, and Africa, with a detour via Roald Dahl in the middle.

And, of course, look around at current novels, retellings are a popular thing to do, whether it’s just taking the characters and dumping them into a whole new situation (such as Rick Riordan with his Percy Jackson series) or the full story, but with nuance and emotion (such as Circe by Madeline Miller).

One thing to keep in mind, is that not all your readers will have the same level of knowledge as you when it comes to the story you’re retelling. Even within my critique group of four, there are two of us who are pretty well-read on western-European fairytales and myths, one who’s more familiar with Central and Eastern European tales, and one who’s not really had anything much to do with either.

Some things you think are obvious might need explanation for someone who grew up in a different culture.

As a final aside: character names. Especially if you’re working with mythology, rather than fairytales, these can be confusing and frustrating. Writers are generally advised not to have character names that start with the same letter. And yet we have stories involving Artemis, Andromeda, Ares, Arachne, Ariadne, Athena, Atlas, Adonis, Apollo, Aphrodite, Atalanta, and Asteria. Or Hera, Heracles, Hephaestus, Hecate, Hermes and Hestia. Welcome to Greek myth retellings.

My suggestion here is to really dive into your characterisation. Make each character so distinct, their voice so clear, that the Greek obsession with certain letters of the alphabet becomes less of a bug and more of a feature.

As a re-teller of fairytales and myths, you’re continuing a tradition as old as humanity, from the stories around tribal fires, to the ones shared by the hearth of a medieval cottage, written down by scholars and adapted for Victorian children, then further floofed by Disney. They evolve and change, because the world they’re told into has changed. The warnings about not going into the woods are now redirected to the dangers of dark city streets. The triumph over an oppressive situation may now be about a toxic workplace, rather than an evil stepmother. And yet those stories can still recognisably be Little Red Riding Hood and Cinderella.

How can you dig into an old story and make it yours, while celebrating the human core that pulled you to it in the first place? I’d love to read what you create.

~

About Kat

Kat Redfern is a fantasy author who writes fantasy fairy tale retellings, and contemporary spins on ancient myths, with strong-minded protagonists, found families, and just a touch of romance.

Her writing is inspired by a lifelong love of mythology, folklore, and escapist storytelling. A balance to her other life as a digital marketer (which she also enjoys).

Kat currently lives in London and can often be found either listening to live music, or poking about a museum or ancient building.

Visit her Website

~

Sackcloth and Sky

A clawed prince. A deal with a djinni. A wounded soldier she must not fall for.

In the city of Carra, gateway to the Southern Desert, Lyra’s life is quiet and small. Trapped in the household of her selfish and ambitious but dim-witted, merchant brother, Khalik, she finds purpose in Carra’s healing sanctuary. But then Khalik makes a new friend…the clawed prince.

Lyra’s beauty is the draw, and as part of a bargain with her brother, Prince Altair presents her with a series of ever-more ornate and beautiful dresses. But even bargains have a price, and the cost will be Lyra herself.

~ ~ ~

Thank you so much, Kat, for being a guest on this blog and sharing your insights. As a lover of retellings I found this such a great read!

Interested in being a guest on this blog? Visit my Guest Posting page, read the requirements and then fill in the Google Form listed there.

Happy reading

Want to find me on Insta? Join my Newsletter? Follow the Podcast?

Then visit my LinkTree to find everything

~ ~ ~

Source: Photos and related pictures supplied by and copyright to author Kat Redfern

Blog Title Images from Canva

© Ari Meghlen. All Rights to the works and publications on this blog are owned and copyrighted by Ari Meghlen or their respective owners in the case of guest posters and podcast cohosts. The Owner of this site reserves all permissions for access and use of all documents on this site. NO AI TRAINING: Without in any way limiting the author’s exclusive rights under copyright, any use of this publication to “train” generative artificial intelligence (AI) technologies to generate text is expressly prohibited. The author reserves all rights to license uses of this work for generative AI training and the development of machine learning language models.

Interesting article and topic.

Thank you, Andrew. Glad you enjoyed it.

You’re welcome, Ari.